Adi Nes Biblical Stories

Wexner Center for the Arts The Ohio State University

February 2 – April 13, 2008

Nationhood is a luxurious affront to those with no home: first comes survival. As a project with an Israeli pedigree, Adi Nes's Biblical Stories mines the Old Testament, a source of his nation's ethical substrate, to produce a remarkably resonant study of the look of dispossession as it descends on the faces of his compatriots. His Biblical Stories (fourteen separate portraits, eleven of which are exhibited here) offers a more diversified panorama than his earlier work, which focused almost exclusively on depictions of masculinity within contemporary Israel, and though the Old Testament abounds with testimonies of heroic individual and collective attainments within the saga of the Jewish people, Nes sees (and so visualizes head-on) these narratives as parables of adversity and expulsion.

The literary critic George Steiner once wrote that the triumph of modernism in Western culture could be defined in terms of the withdrawal of the Old and the New Testaments from the common currency of recognition among an educated, if not necessarily religiously observant, public. But despite Israel's uncertain, and certainly not unopposed, path towards conducting itself as a secular society, the Old Testament remains its commanding urtext, a living trove of stories and testimonies giving the nation nothing less than the origin and early history of its people. Nes reads these stories in terms of the great Jewish themes of exile and exodus, themes that would animate his Biblical Stories when he became preoccupied by the daunting extent of indigence and homelessness he'd come to experience in his hometown of Tel Aviv.

As in such earlier series as Soldiers (1994-2000), Boys (2000), youths (2001), and Prisoners (2003, a controversial commission from Vogue Hommes), Nes produced the Biblical Stories through painstaking preproduction, as though doing a film: he casts nonactors, scouts locations, determines costume and production design, and then photographs the resulting fully staged tableaux. To that extent Nes joins artistic common cause with the likes of Jeff Wall, Katy Grannan, Lorna Simpson, Philip- Lorca DiCorcia, and others: his photographic portraits or scenes, like theirs, result from elaborate contrivance once regarded as inimical to the "natural" aspirations of the reality-reproducing medium.

Nes further inflects his portraits by often modeling them on art historical precedents, an instinct strongly recommended for the Biblical Stories series by the tradition of European old master painters reinterpreting characters from Scripture through the use of contemporary models (the sly and louche Caravaggio being the exemplar closest to Nes's heart). Nes in this sense is as engaged in a dialogue with how visual artists have rendered the human subject as he is with the street-level realities of daily life in a state founded on socialist ideals worn down by the claims of Middle Eastern realpolitik.

Each of the portraits is "Untitled," with a parenthetical designation giving the name of the Old Testament individuals depicted, and for viewers for whom the Bible remains a living book, the characters, as it were, come to life with an almost shocking vividness and clarity. The two women on their own, scavenging for survival (modeled on Dean-Francois Millet's 1857 The Gleaners), are Ruth and Naomi as they walk among us today, enacting the parable's beautiful testament to fidelity: "Wherever you go, I will go, wherever you will live, I will live. Your people shall be my people, and your God, my God. "(Fig.3-4) The prophet Elijah, saved from starvation in the wilderness by the ministration of ravens, becomes a cast-off old man, still wise (or bereft of his faculties?), sprawled on a stone bench (one of the visual sources being a photo taken in 1950 Hungary by Werner Bischof, of one of the thousands still homeless during post-World War II resettlement). (Fig.s) The priest Samuel harbors Saul, Israel's first king, whose defiance of God's commands would then spell his downfall in the only picture within the Biblical Stories framed in such a way as to omit any indication of a contemporary echo or application (Nes modeled it on a detail from Ilya Repin's 1885 Ivan the Terrible Kills His Son) .(Fig.i)

Banished by Abraham with her son, Ishmael (from whom would descend Islam's Prophet Mohammed), the handmaiden Hagar prefigures (and, by Nes quoting it, looks back on) one of the last century's iconic photographic images, Dorothea Lange's 1936 Migrant Mother, the emblematic condensation of the Great Depression in the united States. (Fig.6) His life still seemingly before him, the fragile young boy Joseph sports a multicolored piece of apparel he's soon to loose when his brothers strip him of it and consign him to slavery into Egypt. (Fig.7)

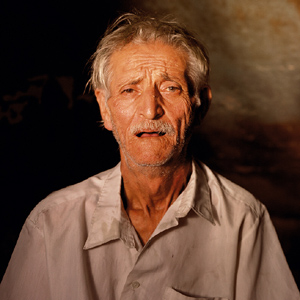

At the opposite end of his life-span, the elderly Dob (Nes's uncle in real life, a substitute for the artist's father who'd recently died) faces the camera either gasping for breath or aching to speak, and, in a pendant image, joined by the three other old men who would listen to Dob's lament, perhaps veterans or survivors spending day in and day out rehearsing the blessings and afflictions of the times they've seen. (Fig.8-9)

All of the Biblical Stories portraits were shot in marginal sections of Tel Aviv where Nes had been unable to avoid witnessing rifts in the social fabric based on income disparity, where the promises broken by the Promised Land had become undeniable. As he's said, "In the new series, I deal with people whose identity is being erased by society, by economic and social forms of integration taking place both in Israel and all over the world." It's within this background of urban blight that the primal rivalry of the brothers Cain and Abel is visualized, a vicious dogfight (he cast both men from an Israeli "no rules fighting" league, and reportedly both of them balked at playing the defeated Abel), with the struggle itself suggested by Titian's 16th-century version of it and the image of the vanquished Abel evoking Peter Paul Rubens's rendering of that moment. (Fig.2, see also Fig. 10)

The assertion of the masculine will to domination within the Cain and Abel pictures and the double-portrait of David and Jonathan form the strongest link to Nes's revious all-male series. As a gay artist, Nes remains uniquely eloquent on how traditional notions of masculinity are configured within Israel's visual conception of itself, and the brutality of the Cain and Abel panels are countered by the forthright lyricism of David and Jonathan's presentation. Even after making such allowances as could be fairly granted for the existence of ambiguity and metaphor within biblical discourse, the story of David and Jonathan as recounted in the Book of Samuel constitutes the Old Testament's most impassioned and insistent rendition of homoeroticism among men, invoked as such within classical legend and art. Sent into exile by Saul (whom he would be destined to replace as king), and forbidden to see Saul's son, Jonathan, David here shelters Jonathan, the latter cradled in his arm like the lyre David has often been depicted as holding within devotional portraiture of him. (poster) For Nes, it's an image of unapologetic tenderness, two boys together clinging within a graffiti-scarred underpass.

When the Biblical Stories series was on view at Jack Shainman Gallery in New York in 2007, a journalist asked Nes what he had discovered in the course of producing it. He responded this way:

When I started the project foux years ago, I wondered what happens after everything's been erased. If I ignore that I'm gay, I ignore that I grew up in a Sephardic family, I ignore that I grew up in a development town, I ignore that I'm an artist-what is the main thing in my own identity? I thought that the first layer that would exist is Judaism-that I can't run away from my Jewish identity. But when I finished the project, I found a different answer. I found that humanity, friendship, and being generous and compassionate, these are the last things that I have as a human being.

Literally and multiply a born outsider, Nes has expressed ambivalence when asked to comment on the "Zionist project," and certainly artists ought not to be parachuted into zones to fight other people's battles. Nonetheless, Nes's Biblical Stories do expose the moral-ethical dilemma produced when the state descends to instrumentalizing its foundational narratives for purposes less compassionate than nationalistic. Expressing himself as a visual artist, Nes speaks the voice of his people, whoever they are (Kurdistani? Iranian? Jewish? Israeli? gay?), and still one recalls the words of Hannah Arendt, in an exchange in 1963 with Gershom Scholem, that "the greatness of this people was once that it believed in God, and believed in Him in such a way that its trust and love towards Him was greater than its fear. And now this people believes only in itself? What good can come of that?"

Bill Horrigan

|

|

||

|

Noah |

Cain & Able |

Abel |

|

|

|||

|

Jacob & Esau |

Hagar |

Abraham & Isaac |

|

|

|||

|

Saul & Samuel |

David & Jonathan |

Joseph |

|

|

|||

|

Elijah |

Ruth & Naomi |

Ruth & Naomi |

|

|

|

||

|

Job & Friends |

Job |

||