THOUGH NEVER explicitly sexual, Adi Nes’ work explores the myths of

manhood and underlines the latent homoeroticism of military culture. His

photographs capture the honest affection that can exist between men. There is

potency, but there is also melodrama; every picture is presented as a

double-edged sword. For instance, in his image of Israeli soldiers asleep on a

bus, is this merely one artist’s romanticised version of the aggressive male,

or are the men icons of golden youth portrayed, as the artist says, “like

lambs being led to the slaughter”?

In all his photographs, Nes finds a sense of theatricality beyond

realism. His scenes are carefully staged, using models, costumes, flattering

lighting and makeup. Allegory and satire come into play, though at first glance

the images might seem simple and direct. A preening soldier wearing a yarmulke

resembles a circus strongman; one of four recruits pissing in the desert glances

his mate. Nes’ messages are subversive, and often laced with humour. He never,

however, skims over the real horrors of combat and poverty.

The son of Kurdish and Iranian immigrants, Nes grew up in the

underprivileged development town of Kiryat Gat. He was always aware of his

‘otherness’. Now in his late thirties, he has been married to his partner,

poet Ilan Sheinfeld, for 10 years. “When I was a boy, my mother was a

librarian and there were always a lot of books in the house,” he said in a

recent interview. “I formed a close attachment to Greek mythology and I

developed a skill for deciphering the texts and looking for the homoerotic

element in them, which at the time was called ‘friendship’. In my

imagination, friendship was always something else.”

Nes has borrowed several themes from Greek mythology— eternal youth,

the unblemished warrior, self-sacrifice for the homeland. Many of his models

subtly mimic the poses of figures in paintings by Caravaggio, Leonardo and

Michelangelo, while his work also dismantles some of the stereotypes of Israeli

identity. Set in military camps or poor housing estates, the handsome young

extras are transformed into classical gods, dressed in khaki, dripping with

sweat or sprawled across each other in exaggerated tenderness. His scenes from

daily life tease the boundaries of what is permitted and what is forbidden. Nes

represents covert and coercive intimacy: “In my photographs I say that the

homoerotic potential is part of life and part of the street... I want to place

the invisible heroes to the front of the stage.”

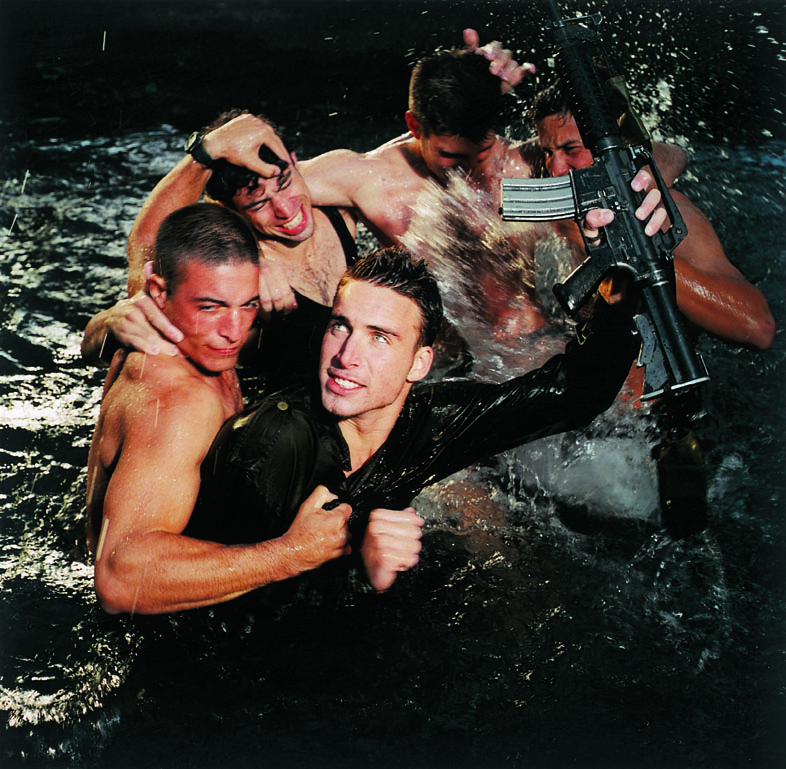

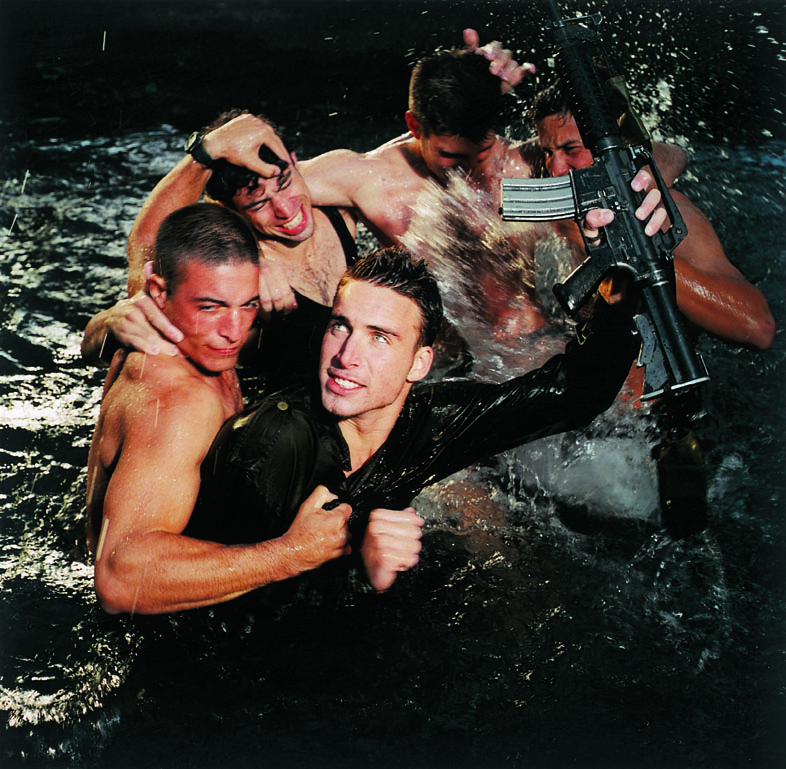

Like all Israeli men, Nes completed three years of compulsory military

service and he reinvents this world of army fatigues, macho camaraderie and the

rites of fraternity in his pictures. Essentially, he eroticises the definitions

of manhood. He is often inspired by journalistic photographs of Israel’s wars,

including an old cover of Life magazine, which Nes re-staged in a scene

where a triumphant soldier holds his rifle aloft as he wades through water with

his frolicking mates.

“Are these men the rugged, tough, invincible Israeli soldiers of 1967

legend,” asks Susan Goodman in the catalogue for a show in New York’s Jewish

Museum, “or are they pretty boys posing and letting off steam, albeit with an

ironic twist of fate thrown in?”

With a growing series of exhibitions to his name Nes is suddenly in the art-world spotlight. His work seen as providing a strong, yet undeniably sensual, vision of dissent. When he was awarded a prize in 1999 by the Israeli Ministry of Science, Culture and Sport, the judges’ report cited Nes’ ability to pull “rejected and repressed representations of Israel out of the drawer ... embodied in his work in the form of homosexual masculinity”. Heady stuff indeed. In any case, as revealed by his eloquent photographs, Nes serves as a bridge between the past and the present, showing how hope and love can shine, even in a climate of tragedy. And as he says, he is trying to be “a small, smart army” all by himself.